Insights from Dinosaur Comics

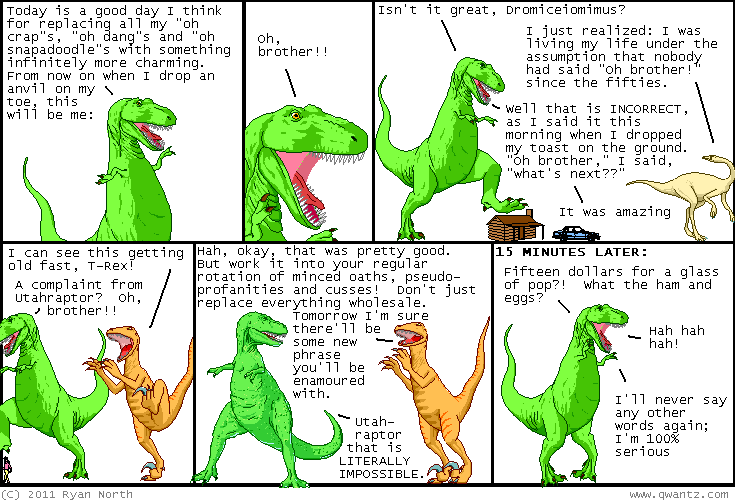

First of all, read this:

It’s from Dinosaur Comics, an online comic strip by a guy named Ryan North, who seems to have all kinds of insights that happen to be pertinent for making and distributing music today. This comic in particular neatly summarizes and/or makes a fable of something I’ve come to wholeheartedly believe, and has informed nearly all of my musical decisions in the past few years.

That something is that making dogmatic, blanket statements about more or less anything is a waste of time, and can be exceedingly counterproductive. I think most people already know this, yet a lot of composers still tend to write in a way that makes me think they don’t really get it (not naming names). I used to be guilty of it…I’d come up with elaborate systems to write pieces, make arguments for why certain pitches “had to be used there, to protect the integrity of my aesthetic ideal” or some crap like that. At some point very early in grad school, while I was making some argument of why I had picked the notes I had picked (which sounded, frankly, ridiculous), my professor Rob Keeley said something to the effect of, “well that’s all great, but let’s focus on what it ends up sounding like.” That was a big revelation to me at the time. I started attempting to write things just by feeling out what would sound good (by my estimation), and stopped ruling things out that didn’t fit “the system.” And oh man did my music improve. Like ten thousand fold. Not to be cocky, but if you’re reading this blog, you’ve at least got some interest in what I’m writing or have heard of me somewhere or another. Trust me, it’s not because of my earlier pieces.

Now, why do we get stuck in whatever dogmatic way of thinking about music that we get stuck in? I think we’re trained to do it in music school. A lot of music history textbooks seem to believe that there is a singular storyline to the development of music, and it largely has to do with music becoming more and more expressive and free (read: dissonant) over the course of history. I won’t argue that our Western music hasn’t become more “free” over the course of history, but in adopting this perspective we do the exact opposite of freeing ourselves. We read a development of one very specific type of music. I would instead like it if music history books said, “Western Classical Music has become more dissonant and expressive over time. There are a million other types of music that you should probably listen to as well, if you want to consider yourself well-versed in all of the sounds available to you as a composer, and REALLY want to come up with something new. Because Western Classical Music is largely just a watered-down codification of things that have been done elsewhere.” You can lambast me for that last line, but look at why people give so much credit to Bartok, Stravinsky, hell even Mahler, for using folk musics. They took something great and incorporated it into what listeners of their time were expecting…to sit in a familiar setting (the concert hall) and hear a familiar instrument (the orchestra).

This isn’t only true for WCM though. If you were raised playing nothing but 4/4 rock in a garage with your friends, then that was your music school. And odds are, as you discovered new and different musics, you pulled aspects of it into your rock band. There’s nothing wrong with any of this. I just think that being aware of it is really really important to writing music that isn’t watered down, and does all that it can do. Blow away the boundaries we’ve artificially set up between these musics, and just do whatever sounds good to you! This sounds dogmatic, but the belief can be applied pragmatically. If you’re writing for orchestra, and want to add something completely external to the history of orchestral music, do it! If you’re writing for a rock band that normally plays tonal music in 4/4 and want to add some Inuit throat singing, go for it! With the technology available to us and the realization that all sounds can be heard as music sounds (it’s all just vibrating air, people), we can really do absolutely anything. So why limit ourselves? And why define ourselves in a way that can keep us from writing the most powerful music possible?

A lot of composers and musicians, thankfully, do indeed seem to realize this. It seems to be the case for everyone on New Amsterdam records, and a lot of outsider rock bands (and big ones, i.e. Radiohead). But it can apply to even more, not just to the all-important sound itself. Again, Ryan North of Dinosaur Comics seems to have this one in the bag, from his recent interview with Smithsonian Magazine:

Being online works really well for any creative work, but especially comics. You have to recognize as a creative person that not everyone’s going to be into what you’re doing. Let’s say 1 in 10 people likes my comic: that means if it’s printed in a paper, 90 percent of the audience will say, “What is this? The pictures don’t change. That’s terrible and now I am physically angry.” Anyone who publishes it is going to get letters about it. But online, that one in 10 can self-select, and when they find my site they say, “Oh man, this is great, this is unlike anything I see in the paper. I’m gonna show this to my friend who shares my sense of humor.” I’d rather have that reader, who loves it, than ten times the number of readers who don’t like it, who read it just because it’s there.

I think we could all learn something about distributing our music from this. Yes, the internet is powerful, and yes, we can all now put a full length record on iTunes all by ourselves, without the help of a label. Perhaps I’m about to get slightly dogmatic for my own taste, but screw it, I’m enjoying writing this. (<—THAT’S THE POINT OF THIS WHOLE BLOG ENTRY.) Why do we still think of releasing music in “albums?” When I was a kid, I would hear a song on the radio, then spend $12 to get a CD of songs I might or might not like just to have access to that one. I don’t make much money these days, and that’s now a pretty big risk. I could be wasting $11 out of those $12 dollars! With how easy distribution is these days, and with the fact that physical media (CDs) is on the way out, why do we still feel we have to release things in collections? Perhaps this is a relic from the having grown up with CDs. Producing and pressing CDs is expensive and most people in stores will ignore yours. Releasing singles digitally is cheap, and gives interested people what they want. I think the market is largely headed towards singles, and towards all music being free to listen to, so we’ve got to catch up with that and find other ways to survive. We have to adjust to the listeners. Not in the music itself (don’t pander in your art), but in the way that people can access it.

Now, I personally have a CD out, and that’s for two main reasons. One is self-gratification. The other is that it’s helpful in getting commissions and whatnot. The reason it’s helpful in getting commissions and whatnot is that the people doing the commissioning tend to be of a previous generation that still likes their CDs. I’ve been very interested in impressing these people, because they’re the ones who decide if my concert music gets played. In a bit of news I haven’t shared on the website yet, I’ve been appointed composer-in-residence for L’ensemble Portmantô in Montreal. Besides being beside myself with excitement, it means I now have a group of excellent musicians to perform and record my music with. It also means that I can stop putting so much effort into networking and finding performers, and can focus more on writing good music. It also means that I really, really don’t need to put out CDs anymore. I probably still will (see “self-gratification”), but I feel like I (and the world of my music) no longer have any real reason to. I’m not going to make any significant income on them, and if a listener really wants one I can always burn one for them. And that feels pretty good.

In college, my friend and roommate Niru once said, “I don’t know about bands anymore. If we want every piece or every album to have its own sound, then why not are we not a different band for each one? Or just go by our own names, as a group of people writing music?” I won’t say that certain perspective enhancers weren’t in play in that conversation, but it’s definitely food for thought. Lately, I’ve been writing concert music, and still playing and writing music for two bands, but have been coming to some sort of synthesis, and it’s causing a minor existential crisis. There’s a drum set playing a dance beat in “Moon Songs,” which is for women’s chorus. Does the drum set qualify them as temporarily being my band? I’ve just been working on a song called “Stop Script.” It’s mostly for electronics, with live guitar and voice. I could play it all myself live. Or I could notate it and give it to some ensemble. Or I could do it with either of the bands I play in, and have us play all of the parts. At this point, I think the band barely matters. I’m the one making the music, the music is the music, and the music is what people will hear. Who cares which of those three possibilities are the final? I personally enjoy performing, so it will probably be some combination of number one and number three, but honestly, I don’t see a reason to decide. Being pragmatic, I think having all three options open, and choosing by the situation, is the way to go.

We’re set up to have this not work though. ASCAP will require a crazy amount of paperwork (I think) to have me be the writer on all three versions. Sound Exchange will definitely screw up the royalties. iTunes and CDDB won’t know what to make of the genre. They’re just as locked in as anything else I’ve been talking about. It’s a systemic nightmare, and to be honest the only answer I can come up with is “screw it, let’s just play some music.” I think that will work for now.